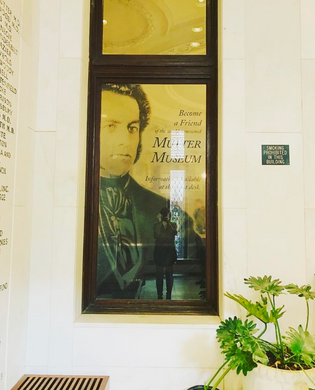

The Mütter Museum at The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Medical history museum with anatomical specimens, models

Medical history museum with anatomical specimens, models

"The Mütter Museum is like nothing else. Though it's exhibits might not sit well with those weak (or full) in the stomach, the collection is fascinating. Technically residing within the halls of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, this display medical anomaly wonderland is something you will not soon forget, and pray you don't one day end up in." - J2 Design

"This one-of-a-kind medical history museum houses a staggering—and sometimes eerie—collection, including a cast of conjoined twins Chang and Eng made after their 1874 autopsy, a piece of Albert Einstein’s brain, and Marie Curie’s electrometer." - Regan Stephens Regan Stephens Regan Stephens is an award-winning freelance writer living in Philadelphia. She covers travel, food, and culture for outlets like Food & Wine, Travel + Leisure, People, and Fortune. Travel + Leisure Editorial Guidelines

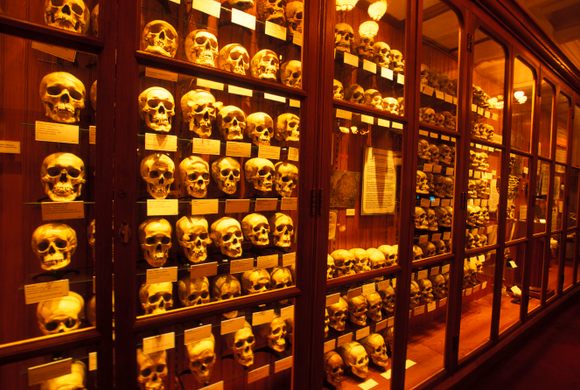

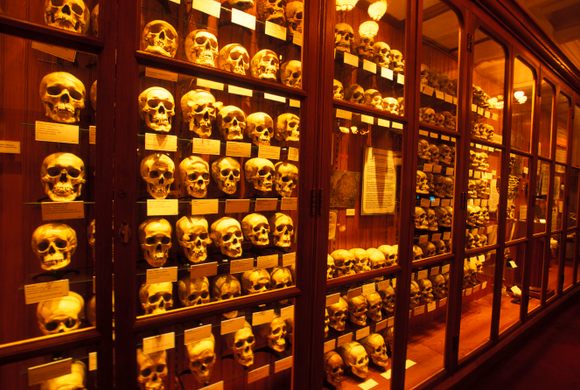

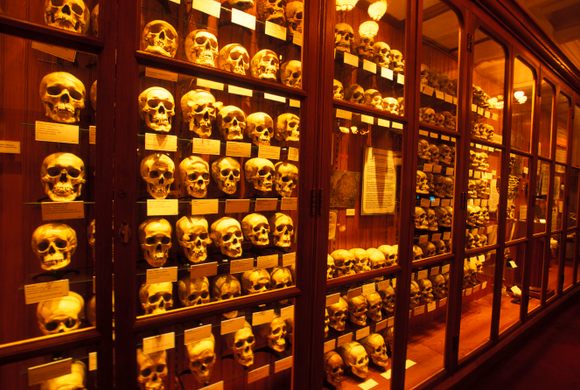

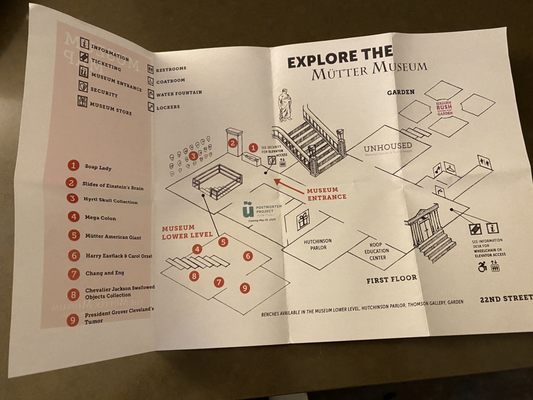

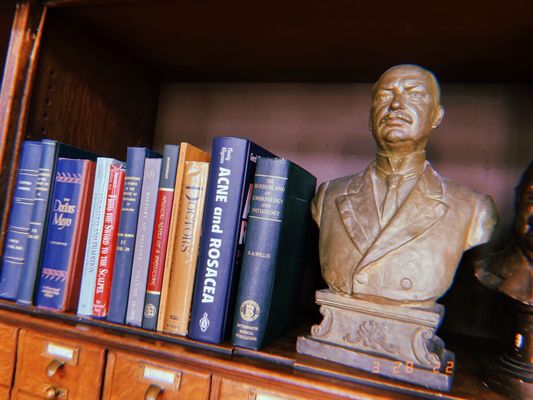

"The Mütter Museum, housed within a portion of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, can trace its origins back to 1858, when Dr. Thomas Mütter donated his collection of medical models and specimens in an effort to honor medicine’s heritage and celebrate its advancements. The museum's 25,000-item collection, spread between two floors, includes everything from medical instruments and wax models, to bones and anatomical, or “wet,” specimens, all ranging from the fascinating, to the disturbing, to the downright disgusting. A few highlights include a Civil War-era set of amputation instruments, a jar of skin from a patient with a skin-picking disorder, and a giant, desiccated colon that'll have you eating kale for weeks. All gawking aside, it’s a true testament to the study and practice of medicine." - Nancy DePalma

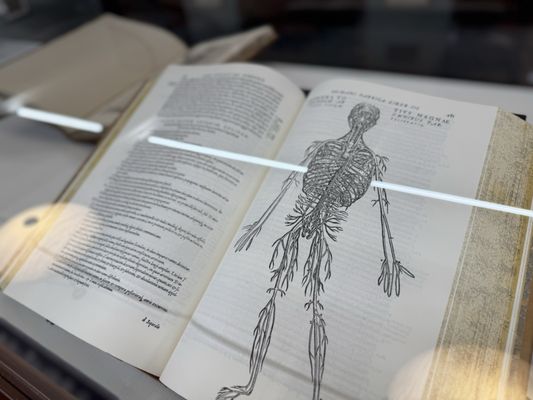

"What's this place about? The College of Physicians was founded in 1787 as a medical professional organization and a place to further the ideals of the medical profession. The College comprises two main parts: a medical library that recently opened to the public on the weekends (it's worth going upstairs to see) and the Mütter Museum, dedicated to medical history. It is named in honor of Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, a fellow of the College, who bequeathed his collection of medical tools and specimens that form the core of the collection. What can you find here? Skulls. A piece of Einstein's brain. A model of conjoined twins. Even a dessicated colon. These are all part of the collection on display. Human health isn't always pretty (note the wet specimens of tumors) but it's all here for the viewing. It's almost always fascinating and often disgusting, and you'll hear plenty of "yucks" from other museum-goers who are transfixed by the cases. Do they hold any special exhibits? One of the most interesting aspects of this museum is how it illustrates how far we've come in the practice of medicine, along with how some things remain the same (vaccine uncertainty, pandemics). The permanent collection is why most people come, but temporary exhibits provide a link between the past and present ("Spit Spreads Death" focuses on the Spanish flu). What's the crowd like? Maybe it's the memento mori theme or the horrifying contents of some of the wet specimens, but The Mütter is listed as one of the top places to bring a date. You'll see plenty of couples, along with families and tourists. On the practical side, how were the facilities? The museum is tucked into a corner of the College building and set over two floors. It's a historic setting with narrow spaces in parts, and the space can get crowded. Gift shop: obligatory, inspiring—or skip it? It's a fun stop, especially for your dark humor-loving friends. What if we are time- or attention-challenged? This is the kind of place where you can breeze through rather quickly and get a good sense of the collection or spend more time imagining what it must have been like to be operated on during the Civil War (hint: don't think about it). If you're here on the weekend, don't skip a trip upstairs to the College's Medical Library. Only recently opened to the public, their display includes rare and valuable books and printed material that will spark your curiosity." - Nancy DePalma

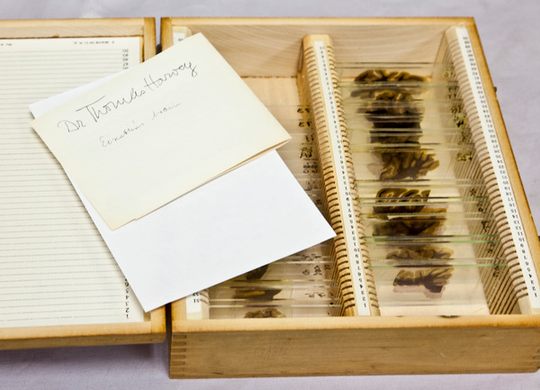

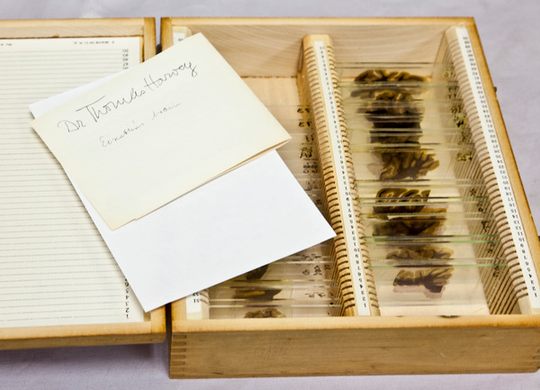

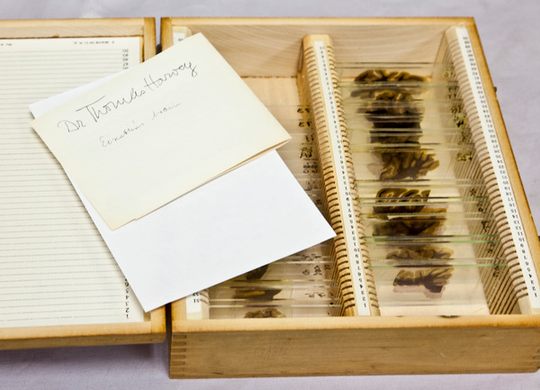

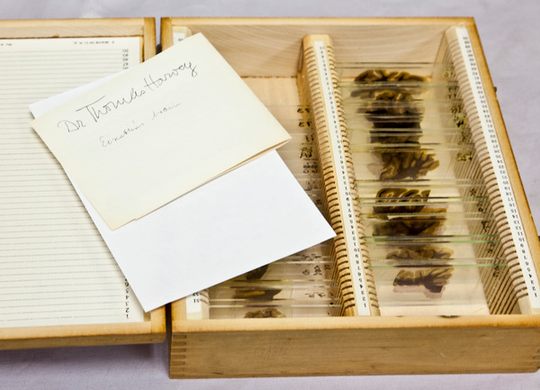

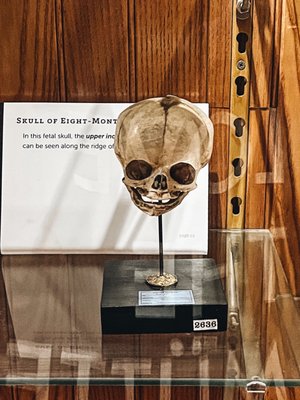

"Located inside the headquarters of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Mütter Museum has a wide range of wondrous and curious medical displays. These include the skeleton of the tallest known man ever to have lived in North America and the fused bones of Harry Eastlack, who died of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva, an extremely rare disorder in which the soft connective tissue of the body ossifies, painfully freezing the body in an immobile state. These and many other exhibitions are displayed in some of the same Victorian cabinets that the museum began with in 1858. Among the extensive collection is a set of brain slides curated not because of its defects, but because of its extraordinary brilliance. They look like strands of kelp, or shards of bark. But in fact, these slides contain slivers from the brain of the 20th century’s most famous scientist: Albert Einstein. Einstein probably wouldn’t have been pleased. He wanted to be cremated, and for the most part, he got his wish. (His ashes were scattered in a secret spot on the Delaware River.) However, the pathologist on duty the night Einstein died in Princeton, New Jersey, wanted to keep the great physicist’s brain away from the flames, so that others might one day study it for clues to his genius. The pathologist, Thomas Harvey, ended up embroiled in drama with Einstein’s family and executor, not to mention the hospital, but was eventually allowed to keep the brain as long as he used it only for scientific study (no tourist attractions allowed). At first, scientists who analyzed small sections of the gray matter saw nothing unusual, but by the 1980s, some began to find intriguing features in areas involved in visual, mathematical, and spatial processing. It turns out that Einstein’s Sylvian fissure (a prominent groove) was shorter than average, while his parietal lobes were slightly wider, and his left inferior parietal lobe richer in glial cells (which nourish neurons). Neuroscientists have theorized that this architecture may have allowed Einstein to think with the kind of “associative play” of images that he claimed was key to his discoveries. However, the typology of Einstein’s brain can never completely account for his brilliance, in part because we don’t know what came first: was Einstein a genius because his brain looked this way, or did it look this way because he was a genius? It’s hard to know, especially without a lot of other Einstein-quality brains available. Meanwhile, this brain—a victim of 1950s-era preservation techniques and Harvey’s many journeys around the country—is no longer in great shape for study. The Mütter’s forty-six microscope slides of the brain came from a Philadelphia neuropathologist named Lucy Rorke-Adams, who donated them to the museum in 2011. She received them from a colleague in the ’70s, who got them from Harvey himself. An octogenarian herself, Rorke-Adams said she wanted to find a safe place for the slides before she passed on. She chose well, and the slides are now one of the museum’s most prized possessions. Easy to miss, but worth poring over, is the collection of 2,000 objects removed from people’s throats, housed in attractive wooden pull out display drawers. These are from the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection, amassed by Chevalier Jackson, who is considered to be the greatest laryngologist of all time. Also of particular interest are the conjoined twin skeletons, delicately displayed in various jaunty positions; the plaster death cast of celebrated “Siamese Twins” Chang and Eng Bunker, who died within hours of each other; the “Soap Lady,” an exhumed corpse from the 1800s unusual for the waxy substance that formed around it during decomposition; and enough horrifyingly-detailed wax models and preserved human fetuses to last more than a lifetime." - ATLAS_OBSCURA